If you’re a Science Fiction fan and you haven’t read this yet, I recommend that you get a copy. If you’re not a Science Fiction fan and you need to be convinced that Science Fiction has something to say about what it means to be human and to struggle, then this is the book for you.

Don’t be misled by the title, ‘Roadside Picnic’ is a gritty, compelling, thought-provoking Science Fiction novella. Although this was published in 1972, in Brezhnev’s Soviet Union, it feels fresh, modern and as relevant today as it was then. There’s nothing escapist about ‘Roadside Picnic’. It’s grim and horribly plausible. It’s only 172 pages long but it’s so immersive and the world it brings to life is so dark that it feels like a much longer read.

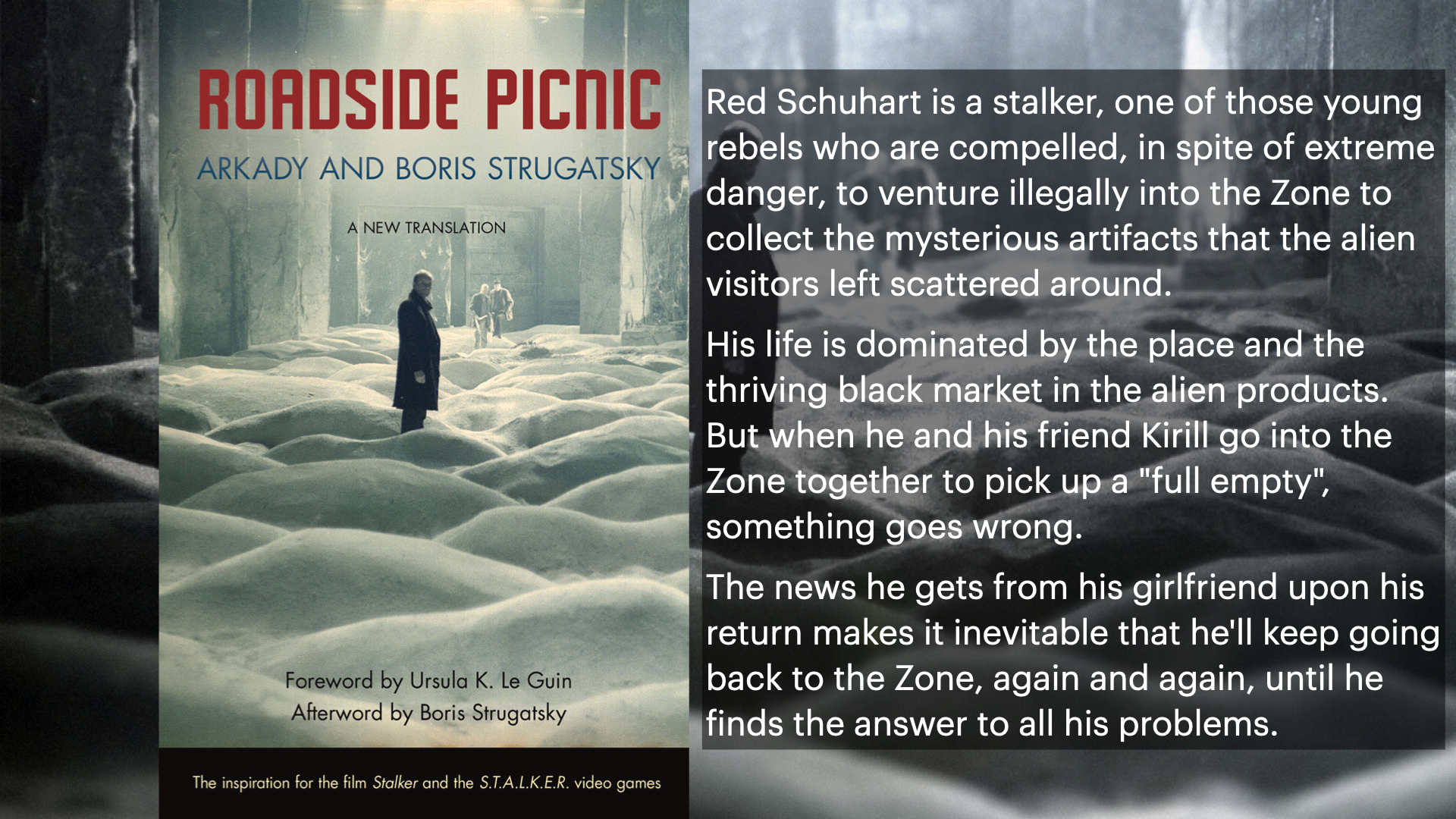

The story takes place some years after ‘The Visit’, the name given to an event where aliens landed at five points around the world, stayed for a short time without making any contact and then departed. Two things soon became clear: the landing sites, known as Zones, had been contaminated in such a way that they produced strange phenomena that were often lethal and that alien artefacts with remarkable attributes lay scattered around the Zones. At the time of the story, the UN has sealed off the Zones to contain contamination and to control access to the artefacts.

The story focuses not on the scientist trying to make sense of the Visit and the properties and contents of the Zones, but on a Red Schuhart. a Stalker, someone who enters the Zone illegally to retrieve alien atrefacts and either sell them to the UN or on the black market.

Red isn’t a hero, he’s a survivor. He’s a pragmatic, smart young man, risking his life to make money by doing illegal things in a lethal environment.

Red is a realist. He knows how the world works. He knows that the only things he can depend on are his own wits and his own courage. He’s powered not by hope but by a determination to survive. He refuses to give way to rage at the unfairness of his situation and instead focuses on taking a deep breath so that he can think things through and avoid making a mistake.

Red gets through his days with the aid of a flask of alcohol and by focusing on providing for his family. We follow him over a series of years as he journeys into the Zone, risking death, betrayal and imprisonment. Red knows that the Zone should be being exploited by scientists to advance knowledge for the benefit of all mankind but that he is helping to pillage it for the short-term advantage of a greedy few who have no regard for the safety of others.

Why does he do this? To survive. He believes that mankind’s greatest achievement is that it is still alive and plans to stay that way. He recognises that the need to survive makes him vulnerable to exploitation by the greedy who see the Zones as a zero-sum game. He would like things to be different but he has to deal with the world as it is.

Red’s struggle is a very human one. He is a man with no resources and no opportunities, running the lethal mazes of money and need, learning to rely only on himself. He is aware of but is detached from the agenda of the scientists and officials. He knows he is being used as a tool by scientists and officials and by the wealthy looking to get wealthier by any means. He is resigned to constantly struggling against bureaucracy and law enforcement and occasionally losing his freedom.

Most of the book is taken up with Red’s struggle. We watch as, year after year, he is ground down by his environment. For a while, he is sustained by his love for his family but even they eventually become as much a burden as a blessing. With no other options left, Red treks into the Zone to find an artefact with mythical qualities that might provide him with a way out, if he can survive, if he’s willing to pay the price and if he can decide what to wish for.

I found Red’s story compelling. It felt real, in a grimy, I’m-so-glad-this-isn’t-my-life way. I’m not surprised that the version of the book published in 1972 had sections removed or changed by the Soviet censors. I’m very glad that the English translation worked with the original text.

So, why is this book called ‘Roadside Picnic’ and not ‘Stalker’ (which was the name used by the subsequent movie and video game)?

The explanation comes during a short interlude in the story that is not focused on Red. In it, a Zone entrepreneur/fixer and a physics Nobel Laureate discuss The Visit over a drunken lunch. The inclusion of this scene felt a little clumsy but the content made it irresistible. The physicist explains The Visit as analogous to a roadside picnic. The aliens were taking a rest stop. They were not there to contact humanity and had no interest in staying. The Zones are just the places where they left their trash. Humanity watched them from afar and is now busy picking over the rubbish and pollution that the aliens left behind, in the hope of finding miracles.

My first reaction to this was – ‘What an original take of First Contact’.

Then my inner atheist cleared his throat and I saw that it was more than that. In a sense, all of human history is a Roadside Picnic, provided you reject the idea of an interventionist God or Gods. Mankind in general and scientists and engineers in particular, have spent centuries picking over the shape of a world created by forces completely indifferent to their existence to find something miraculous that will help them to survive.

The Strugatsky brothers, Arkady and Boris, were writers of speculative fiction in the Soviet Union.

When they were 16 and 8 respectively, they survived the siege of Leningrad.

After serving in the Soviet army, Arkady graduated from the Military Institute of Foreign Languages in Moscow, where he trained as a Japanese and English interpreter.

Boris studied physics and astronomy at the Leningrad State University, graduating from the school’s Mechanics and Mathematics College in 1955. He spent the next decade as an astronomer and then a computer engineer.

Their most famous novel, Roadside Picnic was published in 1972, in a version approved by the Soviet censors. In 2012, the novel was re-released in English in a new translation by Olena Bormashenko, based on a version restored by Boris Strugatsky to the original uncensored state.

This novella sounds just like the thing I love to read. Definitely checking this one out! Thanks for sharing.

LikeLiked by 1 person