I’m a reluctant reader of Maigret. He’s a moody man who spends most of his time locked inside his own head. He treats the people around him as either instruments of his will or specimens to be vivisected. His ‘method’ seems to be to brood deeply, eat and drink a lot, issue gnomic exclamations, bark orders, brood some more and then bring the bad guy to justice.

So why do I keep spending time in Maigret’s company? Because of Georges Simenon’s gift for making unpleasant stories about unpleasant people come to life with simple, concise prose. He has a gestalt style that displays fragments of a pattern vividly but disjointedly, enticing my imagination to fill in the blanks and see a shape that is much richer than the individual slices I’ve been shown. His prose is dispassionate and often brusquely factual and yet he generates empathy as well as insight.

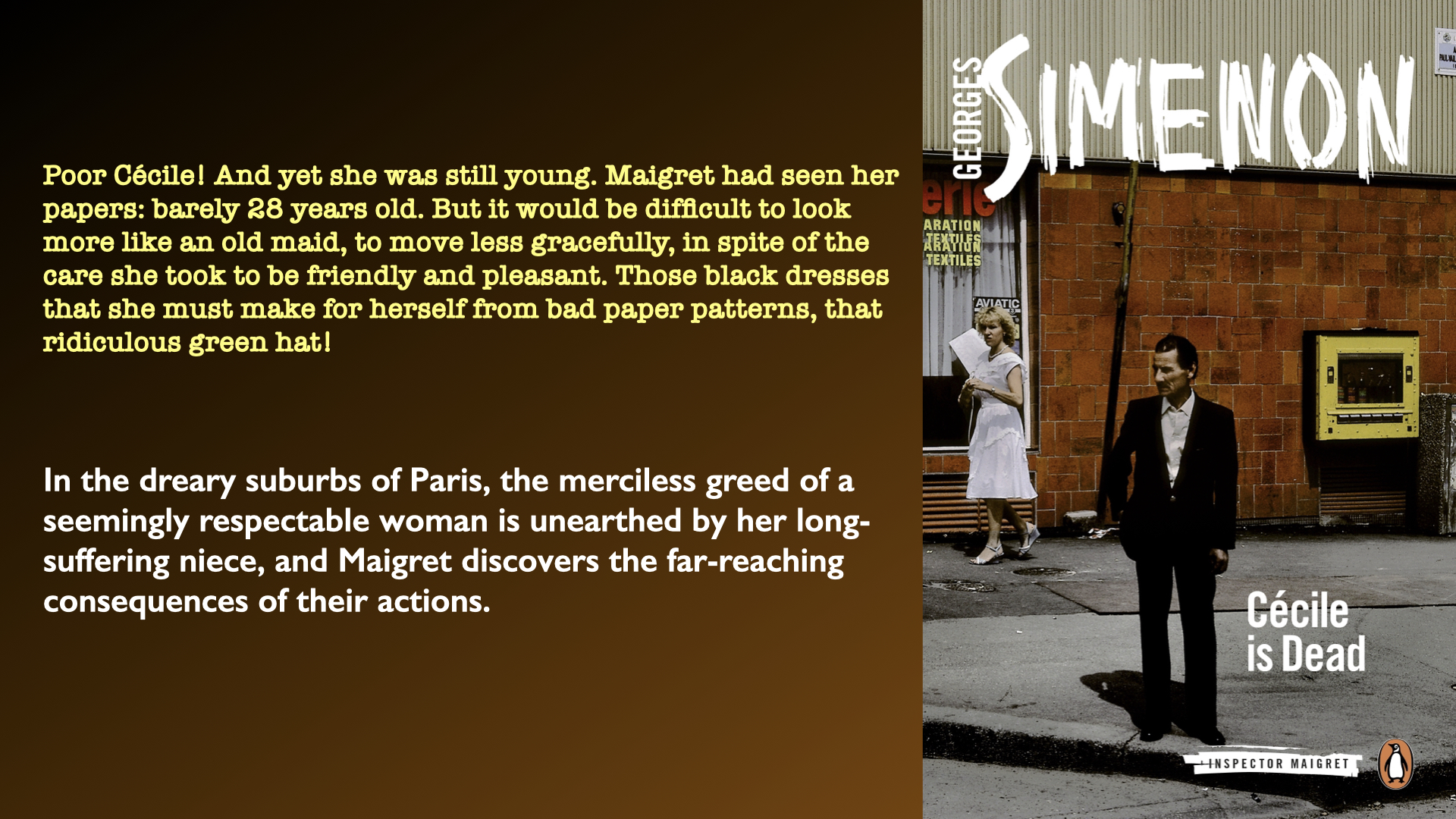

‘Cécile Is Dead’ is a great example of how he works. The plot, such as it is, is about greed, paranoia, desperation and betrayal but the book is mainly about Maigret’s guilt.

There are no long speeches about any of these things, rather they’re displayed in fractured fragments as Maigret figures who killed a miserly old woman in her own apartment in the dead of night.

Yet the old lady’s death isn’t what pushes Maigret into a state of obsessive brooding. He wants to know why Cécile, the old lady’s niece, is dead. He is fixated on Cécile’s death not for what for him would be a normal reason, i.e. that her death is an aberration in the emerging pattern of the crime but because he feels responsible for her death. His whole investigation is a form of penance to expiate the guilt he feels for not having taken the simple actions that would have avoided her death.

I admire how Simenon pulled me into this mire of misery from the first page. Two chapters in and I was already immersed in the seedy, smoke-filled, men-without-women, hierarchical chaos that is Maigret’s police station and my dislike for them was amplified by how they treated Cécile.

When Cécile was found dead and I realised that, this time, Maigret would be driven by well-deserved guilt about the consequences of his detachment, I couldn’t suppress a brief surge of schadenfreude, which is a tribute to how well Simenon has drawn Maigret.

I don’t like Maigret. It’s not that he’s annoying like Poirot, it’s just that he’s so detached from everything except the puzzle he’s solving.

I wasn’t engaged by the puzzle Maigret was trying to solve, mainly because it was clear that, like his colleagues, I’d have to wait for the big reveal at the end of Maigret’s brooding and there was no point in trying to second-guess the outcome.

What kept my attention were the vivid descriptions of the seedy, desperate, poverty-stricken Paris that Maigret wades through. It seemed to me that Mr Charles’ apartment was a metaphor for it all – a decaying, neglected place saturated in an unpleasant smell that is cloying to spend time in and clings to your clothes long after you’ve left.

One thought on “‘Cécile Is Dead’ – Inspector Maigret #22 by Georges Simenon, translated by Anthea Bell”