Today is International Women’s Day. To mark the occasion, I’d like to recommend to you ten books written by women (six American, two English, one Australian and one Irish) that I’ve read in the past twelve months. I’ve picked them because they are books that I’d recommend on their merits on any day of the year, they are all stories with women at their centre and they all made me look at the world differently.

I’ve listed the books in alphabetical order by title and provided a summary and a link to a full review for each book. I hope at least one of them calls to you.

Bad Men is a wonderful mix of violent thriller and RomCom which gleefully twists the conventions of both genres to do surprising things, many of which involve attacking the patriarchy with wit and sharp blades.

This book made me laugh and it kept me guessing. Saffy, our heroine, is a killer who may or may not be a sociopath yet I found myself cheering her on in her endeavours both to win Jonathan’s affections and to rid the world of some despicable men.

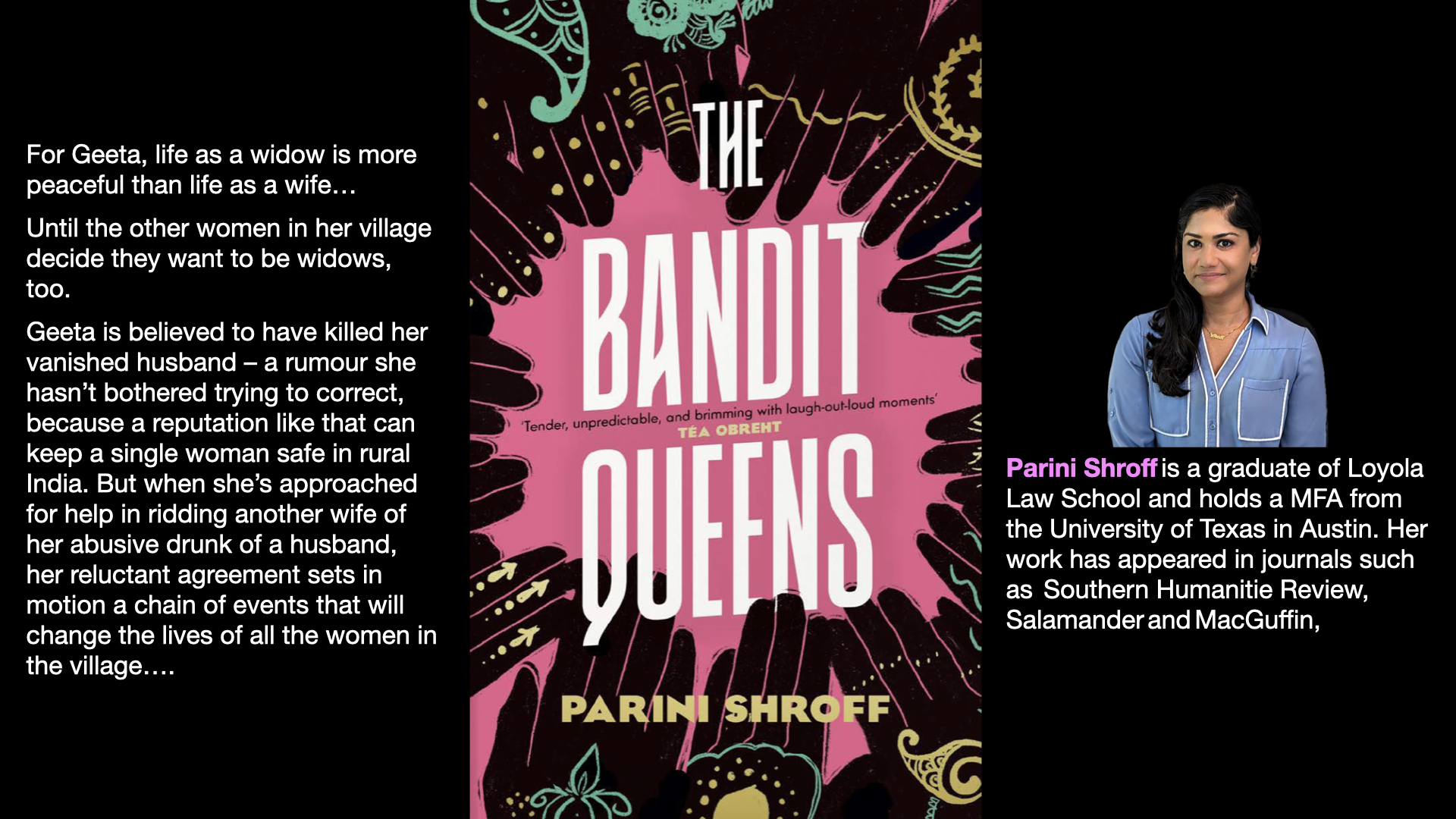

‘The Bandit Queens’ is a rare kind of book: accessible, entertaining, truthful and thought-provoking. Although it may sound like a ‘female killer getting away with it’ narrative set in a village in rural India, that’s not what the book is about.

Firstly, Geeta, the main character, is not really a killer. She is an abused wife who has not corrected the belief held in her village that she ‘removed her own nose ring’ by killing her vanished husband. She’s not a slick, confident Black Widow, gleefully reducing the number of terrible men in the world. She’s a woman who still bears the scars of emotional and physical abuse and who wants nothing more than to live in safety and be left alone.

Secondly, this is not just the story of Geeta’s struggle. Geeta quickly finds herself collaborating with three other women from the village who, together, are the Bandit Queens of the title.

Thirdly, although the story centres around the consequences of the physical and emotional abuse of women, it also looks at other issues that shape the lives of the village women: social exclusion based on gender or religion or caste, childlessness, motherhood, the marginalisation of women by the patriarchy, the negative impact of the dowery system, and the rivalries between the women themselves.

‘The Burning Girls‘ is grim and violent and filled with guilty secrets and deceptions. The start lulled me into thinking that I was reading another story about a haunting in an English village which will threaten the newcomers, the vicar and her teenage daughter, and end with a dramatic confrontation between good and evil. It soon became clear anything familiar about this story was probably a distraction. Yes, there was a haunting going on and yes, the vicar and her daughter were in danger but there was a lot more going on and most of it was twisted and violent.

What I enjoyed most about this book was the way the characters of the vicar and her daughter were drawn. Each of them seemed real to me and the relationship between them was one of the most believable middle-aged single-mom to teenage daughter I’ve read.

‘The Calculating Stars‘ is a remarkable book. Yes, it covers a space program in an alternative history version of the 1950s, following an extinction event, and it does it well, but it does so much more than that. It’s not an ‘against the odds‘ struggle story, although the odds are stacked against Elma York and her desire to go into space. What makes it powerful is that It’s a personal story about loss, mental health, discrimination, family and friendship.

The storytelling made me laugh and cry but never dropped into melodrama. It stayed true to the science without force-feeding me endless technical information and it reflected the politics and prejudices of the time without becoming preachy or sanctimonious.

‘The Calculating Stars‘ won the Nebula Award for Best Novel, the Locus Award for Best Science Fiction Novel, the Hugo Award for Best Novel, and the Sidewise Award for Alternate History. It is the first book in a series that I’ll soon be reading the rest of.

‘Dark Tales’ is a collection of seventeen stories that look at different kinds of darkness.

They’re not horror stories. They’re not built to make the hairs on the back of your neck stand up, at least, not at first.

They’re stories that you recognise immediately as being a little ‘off’ in a way that disturbs you even though you can’t name the source of your unease and the longer that inability to name what is wrong continues, the more disturbing the stories become.

These are stories that wear ordinariness like a mask. It’s an ordinariness that you immediately distrust, a normality that triggers a sort of uncanny valley response that is quietly unnerving.

These stories have barbs that bury themselves in your imagination, making them hard to forget. This a partly because each story has something dark and surprising curled around its heart, partly because I spent so much energy trying to work out what was ‘off’ about each story (think about how tiring it is to be constantly looking over your shoulder for something you know is following you but which you never catch a glimpse of) and partly because some stories never fully explain themselves, leaving my imagination wrestling with the unease that they’ve left behind

I recommend this collection to anyone who wants to read stories that will unsettle and discomfort them and make them think about the darkness that waits below the surface of the things we think of as normal.

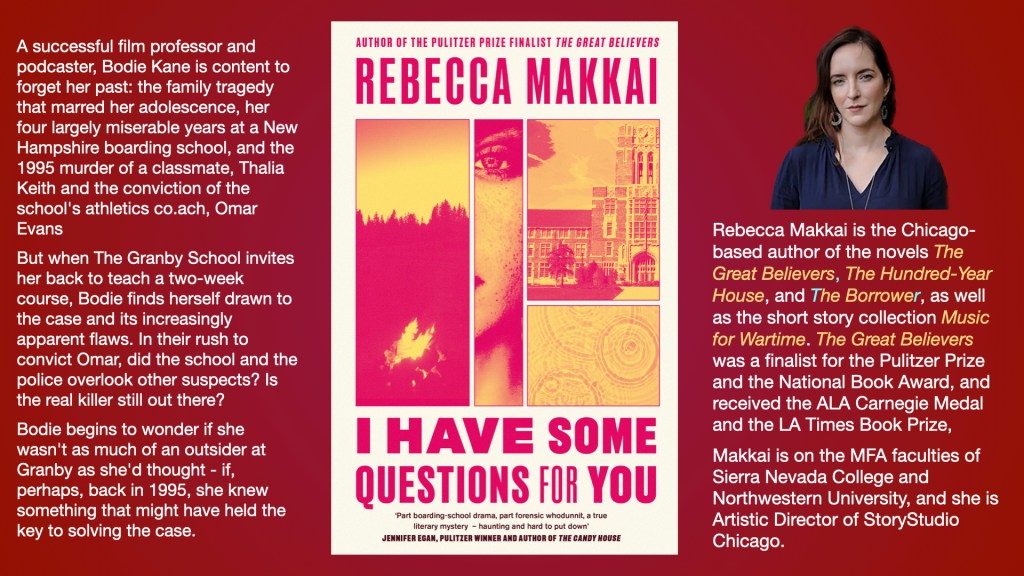

‘I Have Some Questions For You’ is a powerful, thought-provoking, sometimes very uncomfortable-to-read book.

In Part I of the book, the function of the murder mystery was to provide a context for displaying how fragile our memories are, to expose the entropic nature of our sense of self and to describe how our sense of self can deform under pressure. It is set in 2018, the first year of #MeToo, and, as Bodie Kane re-examines her life on campus in 1995 she realises how many misogynistic and abusive actions she glossed over or failed to identify. It was an immersive experience that was also tough going at times because what I was being immersed in was a close-up and personal experience of Bodie Kane coming apart as she questioned everything about her understanding of who she is and who she has been.

The pace of the book changes abruptly in Part 2. A few years have gone by. The atmosphere is now less an anxious ‘Am I crazy to think this? Do I really remember this? Is this all my fault?‘ and more a detached this is out of my hands now. I’ll testify and see where the chips fall.’

By the end of the book, I felt as if I witnessed something real and found myself trying to define what that ‘real’ thing was.

I found my answer not by revisiting the plot twists but by considering the title: ‘I Have Some Questions For You’. The recurring questions in the novel are: How did I let this happen? and How did I not see this?

What I took away from the book was that our lives are only narratives when we make them, or let other people make them, so. We become blind when we let that narrative sit unchallenged. We need to learn to ask questions that enable us to reassess, reject, reaffirm or reshape our narrative. We need to understand that our answers are all temporary and imperfect and need to change over time.

‘Murder On The Red River‘ is vivid, realistic and beautifully written. It’s a personal story of trauma and survival, disclosed around the investigation of a killing. The focus of the storytelling is not on the killing or even on finding the people who did the killing but on immersing the reader into the world of Renee “Cash” Blackbear, a nineteen-year-old Ojibwe woman making her living driving trucks for farmers in the Red River Valley in the 1970s.

We get to see the world as Cash sees it. We learn how she deals with the world and what she expects from it and, as she informally investigates the killing of an unidentified Native American man who was a long way from home, we learn about the childhood she had, being shifted from white foster home to white foster home and of the friendship she built with the local Sherriff, the only person who took any real interest in her welfare when she was a child.

I loved this storytelling style. It was immersive, visual and emotional. There is no separation between Cash and the story. The plot isn’t just character-driven, the plot exists only as the trellis that the vine of Cash’s personality blossoms on.

There is a plot and it’s a good one. It shows not just how a native man from a long way away might come to be killed but how the people who did it might be fairly sure that they’d get away with it.

I liked that the killing and killers are treated as part of the landscape of Cash’s world, as expected as a sunrise and as unsurprising as a familiar horizon. Cash throws her energy into solving the crime but not because she has a need to solve a puzzle or because she wants to be at the centre of the action but because this killing and these killers are part of her world and she can’t let that pass.

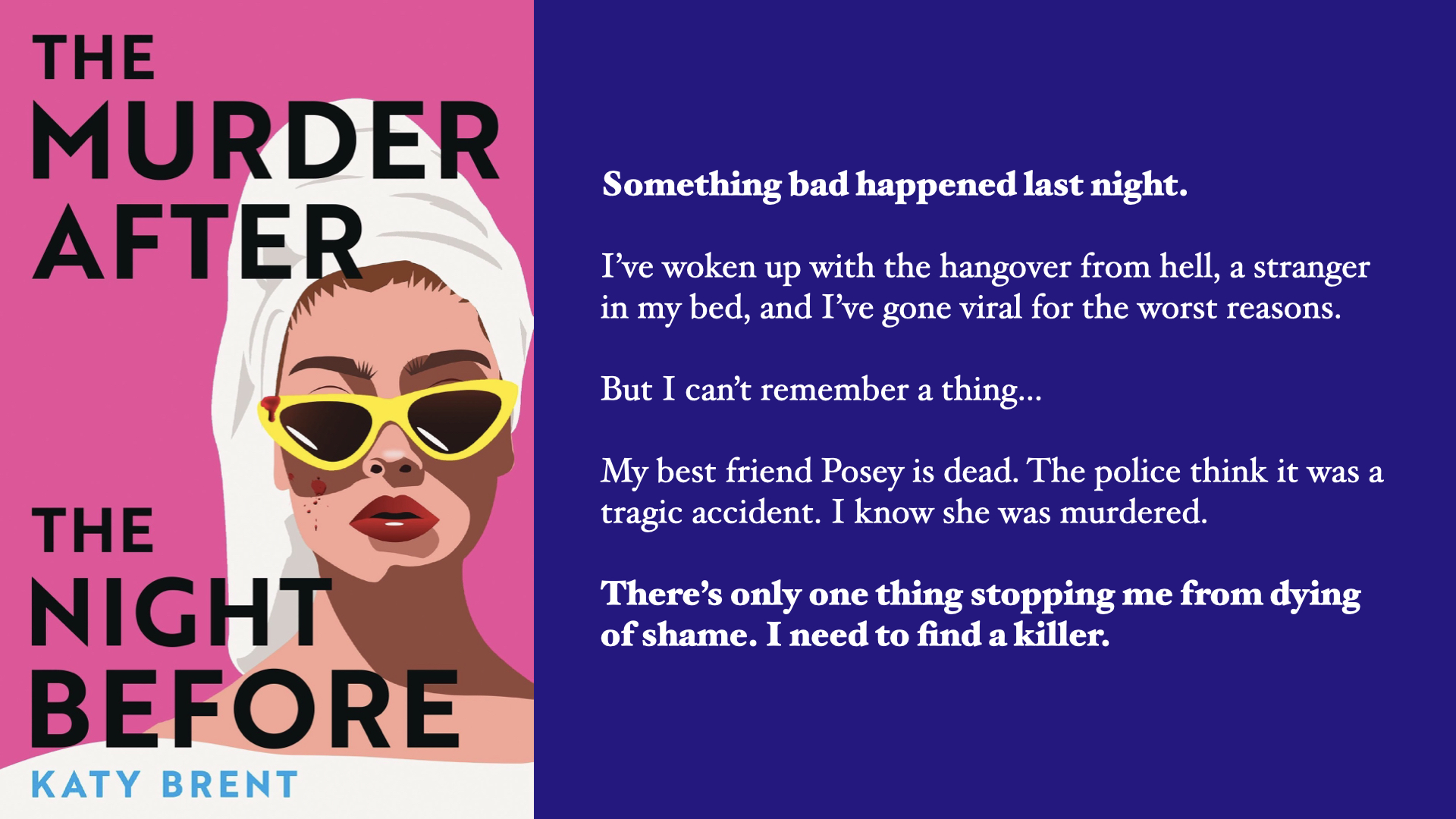

‘The Murder After The Night Before‘ isn’t the light, witty but dark book that the cover and the title had led me to expect. It’s a hard-hitting thriller that delivers the full emotional impact of murder, sexual assault, revenge porn/shame porn, all aggravated by the main character’s habitual binge drinking, low self-esteem, grief and constant simmering anger.

Much of the action is driven by misogyny. There is abuse on almost every page: ranging from gaslighting and old-boy-network cover-ups through online shaming to sexual assault and murder. The impact of all of these things on Molly Monroe is amplified by her history of binge drinking, her doubts about her own mental health, her low self-esteem, her habit of being viciously judgemental when she has been drinking, her social isolation, her grief for her murdered friend and her growing guilt about having at best failed her friend and at worst having contributed to her death.

I was impressed by Katy Brent’s ability to make depression and shame and grief feel so real while still weaving an absorbing, page-turning mystery.

‘Of Sorrow And Such’ is a 158-page novella that packs an enormous punch. From the first page, I fell in love with the clarity of the writing and the deftness of the storytelling. With a light touch, Angela Slatter immersed me completely in the life of the little village of Edda’s Meadow as seen through the eyes of Patience Gideon, a woman who practices her craft without anyone ever actually calling her a witch.

Patience Gideon is a wonderful creation. She sees herself and the world she lives in clearly and doesn’t look away or give in. Even though she knows how brutal and unfair the world can be and how vulnerable people with her gifts are once the priests prod the people into turning against them, she’s still willing to take risks for others. She’s a pragmatist. She prepares for the worst and expects it to happen someday but, in the meantime, she does what good she can, looks after her adopted daughter and tries to open herself to life’s small pleasures.

Things change when Patience finds herself in the hands of men who she knows will take either a self-righteous or a sadistic pleasure in watching her burn. She’s alone and helpless but still full of fight. She does what she can to sow the seeds of doubt and discord among her captors and waits for an opportunity that she knows may not come.

I was impressed by how grimly real this all was. This isn’t an escapist fantasy. It isn’t something where the witch can cast a spell and walk away. Patience’s world is ruled by men. They are not kind. They are not wise. They are not brave. But they have an absolute belief in their entitlement to take whatever they want whenever they can and a complete disdain for women, especially women who are any kind of threat to them or the world as they believe it should be. When the book feels grim, it’s because these men are not demonised characters, too evil and too shallowly drawn to believe in. They are men I recognise. They each have their own reasons for doing what they do and none of those reasons are good.

Patience sees all of this clearly. Has been able to see it clearly since she was a child and knows that while she might be able to protect herself from it or even revenge herself on it, she cannot change it.

I found myself highlighting paragraph after paragraph of Patience’s insights into how her world works. Her words sliced through hypocrisy and bigotry like scalpels parting fat and muscle to expose the misogynistic heart.

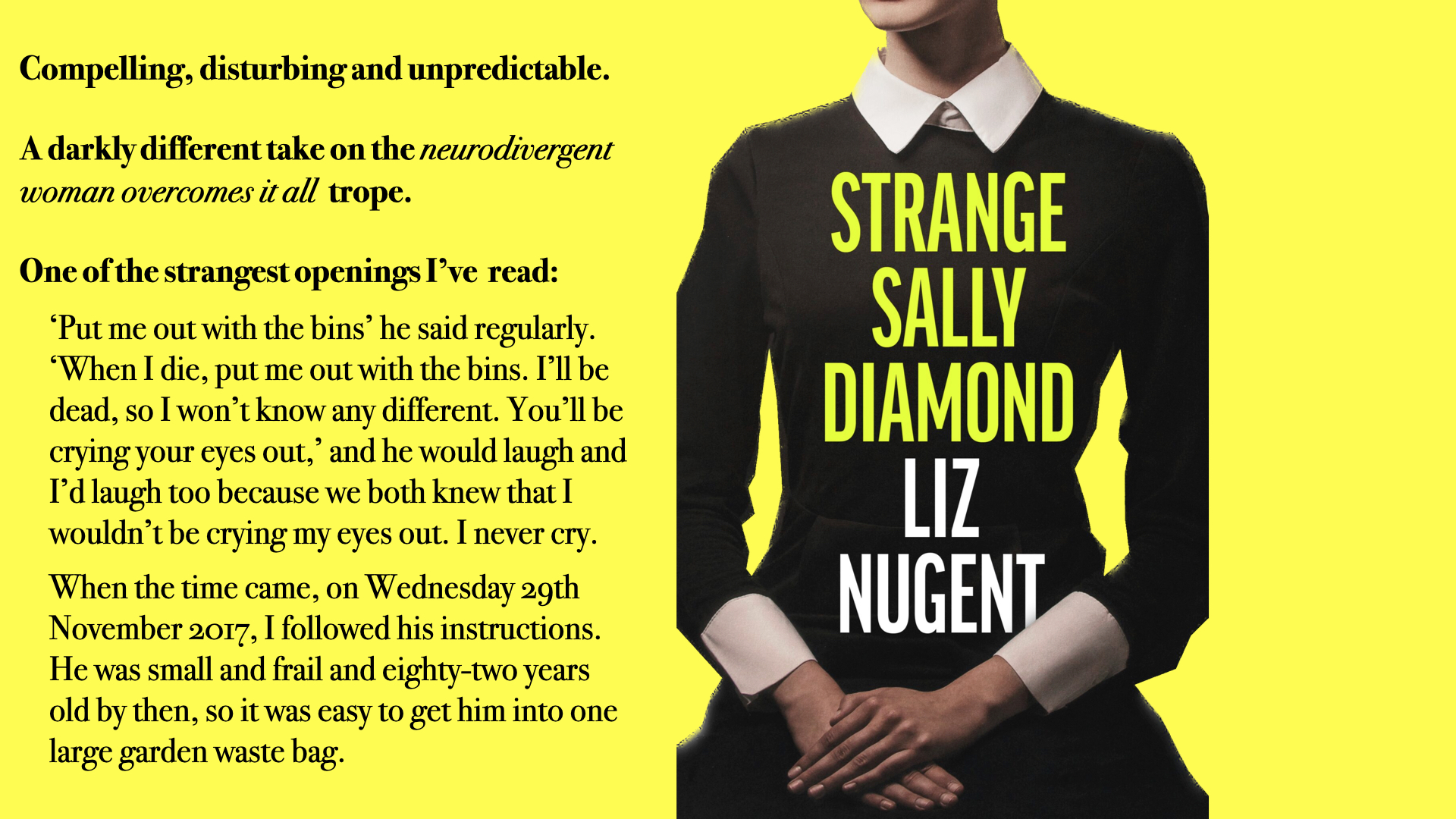

‘Strange Sally Diamond‘ manages to be both compelling and deeply disturbing.

At first, I thought it was going to be a neurodivergent woman overcomes it all novel but it was much darker than that. This is a tale born of blood and pain and hate. That kind of damage can’t be overcome or undone or redeemed, only endured.

Sally Diamond is indeed strange. She knows that. It’s not something that she can change and it’s not something she wants to make a fuss about. She just wants to get on and she wants people to leave her alone.

She’s an Irish woman, who is in her forties when she puts her recently deceased octogenarian father out with the bins, as he had often requested her to do.

The tale of how Sally came to be discovered by the world and to be in need of psychiatric treatment is a very dark and disturbing one, made more so because the way the story is told shows how possible and plausible the evil that it describes was.

What happened to Sally was terrible. What happened afterwards was also terrible only in a more mainstream, accepted by everyone as normal back then kind of way.

If it was mandatory for books to provide trigger warnings on the first page after the title, ‘Strange Sally Diamond’ would have a long list: abduction, rape, child abuse, abuse of power, misogyny, violence, torture and psychological abuse would all have to be included.

None of these things is there to thrill or entertain or to build up psychological pressure. They are there as truths to be confronted and dealt with. They are there because they explain Sally Diamond’s strangeness although they do not define Sally Diamond.

This is a deeply disturbing story that is more truthful than hopeful. It is dark but credible. It looks not at how we make the darkness go away but how we live with what it has done to us. None of the answers are comfortable ones and some of the outcomes are very dark.

So this wasn’t a neurodivergent woman overcomes it all novel, although Sally certainly tried. There may not be a triumph at the end of this book but there is an understanding that not everything can be fixed and that broken things still have worth, especially to the people who are broken.