I’ve just started N. K. Jemisin’s short story collection, ‘How Long Til Black Future Month’.

I’d intended to review the collection as a whole with comments on each story as I normally do, but the first story in the collection sparked so many thoughts that I decided to write a post to help me work through them.

I love it when a short story does that.

Anyway, here are my thoughts. I’m interested in hearing yours.

THE ONES WHO STAY AND FIGHT

In her introduction to ‘How Long ‘Til Black Future Month?‘, N. K. Jemisin talks about how the stories in the collection are “also a chronicle of my development as a writer and as an activist.” She mentions her surprise at “…how often I write stories that are talking back at classics of the genre.” and then says that ‘The Ones Who Stay And Fight‘ “…is a pastich of and reaction to Le Guin’s ‘The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas‘.”

‘The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas” (1973) is a Hugo Award-winning allegorical short story about people who leave a life of safe luxury in the city of Omelas once they understand that it is paid for by the suffering of a child.

I first read it fifty years ago, in 1975. I was eighteen, in my first year at university and fully convinced of my ownability to step outside of conventional thinking. I thought Le Guin’s story was wonderful – challenging and to the point. It made me ask myself if I would be one of the ones to walk away.

Even then, the best answer I could honestly muster was, “I hope so.” Now, my answer would have to be, “Well, I haven’t so far.”

The story made an impression on me. It became a reference point in discussions about ethics. And yet, it was decades before it occurred to me that the motivation of those who walk away from Omelas might have had more to do with keeping their hands clean rather than confronting the ethical problem.

In “Those Who Stay And Fight‘ an unnamed narrator is describing to someone from America, the utopian state of affairs in the city of Um-Helat in a world that is somehow parallel to Earth. Omelas exists in the same world as Um-Helat. The narrator describes it as: “a tick of a city, fat and happy with its head buried in a tortured child”. The narrator acknowledges that the reality of Um-Helas, a city where diversity is valued and all people are treated with respect, is likely to be hard for someone raised in America. This is how the narrator describes the likely American response to descriptions of Um-Helat:

“It cannot be, you say. Utopia? How banal. It’s a fairy tale, a thought exercise. Crabs in a barrel, dog-eat-dog, oppression Olympics—it would not last, you insist. It could never be in the first place. Racism is natural, so natural that we will call it “tribalism” to insinuate that everyone does it. Sexism is natural and homophobia is natural and religious intolerance is natural and greed is natural and cruelty is natural and savagery and fear and and and … and.“Impossible!” you hiss, your fists slowly clenching at your sides. “How dare you. What have these people done to make you believe such lies? What are you doing to me, to suggest that it is possible? How dare you. How dare you.”

This struck me as a typical “I’m a realist and the real world doesn’t work like that” response. For me, the interesting thing was the anger that underlay the response. That’s an emotional reaction that bears thinking about. Is the anger because the world IS like this, or is it because, if it could be different and we do nothing to make it different, then we realists would be guilty of having kept things as they are because we don’t dare imagine them differently?

I won’t go through the whole plot because I’m hoping that, if this post interests you, you’ll read the story for yourself, but I do want to highlight one point in the story that resonated for me and which my eighteen-year-old self might havenot been so sure of. One of the beliefs underpinning Um-Helat’s utopian existence is that evil must be confronted, contained and destroyed. The narrator shares this truth with the American (whose responses we never hear and says:

“Does that seem wrong to you? It should not. The trouble is that we have a bad habit, encouraged by those concealing ill intent, of insisting that people already suffering should be afflicted with further, unnecessary pain. This is the paradox of tolerance, the treason of free speech: we hesitate to admit that some people are just fucking evil and need to be stopped.”

So now I have a new reference point for my discussions with myself. If I admit that ‘some people are just fucking evil and need to be stopped’ what do I do about it?

The most I’m likely to do is talk, but given how afraid authoritarians are of people saying what they think, maybe that’sat least a start.

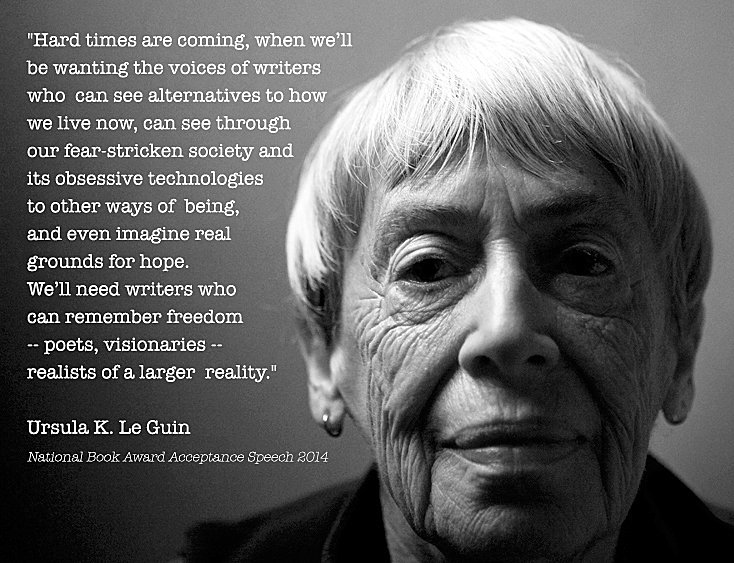

When I was searching to see if I’d ever reviewed ‘The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas‘ I came across a Le Guin quote that I used in a post in 2018. It’s not from her fiction. It’s from her 2014 National Book Award Acceptance Speech.

Here’s the post it came from: